By: Katri Keskinen & Maria Varlamova

COVID-19 pandemic has radically transformed our working lives and the labour market. Many workers have faced a digital leap in their working conditions as workplaces have closed their doors. At the same time, a number of workers unable to work from home have faced temporary or permanent layoffs. In the beginning of April 2020, the International Labour Organization (ILO) estimated that COVID-19 will likely lead to a loss of 195 million full-time jobs globally by the end of this year. For Europe, the estimate was around 12 million lost full-time jobs. While the numbers are based on estimated lost working hours, they only reflect the impact on full-time jobs, without considering those employed on informal, part-time and short-term conditions. In reality, the number could be much larger.

What are the estimates?

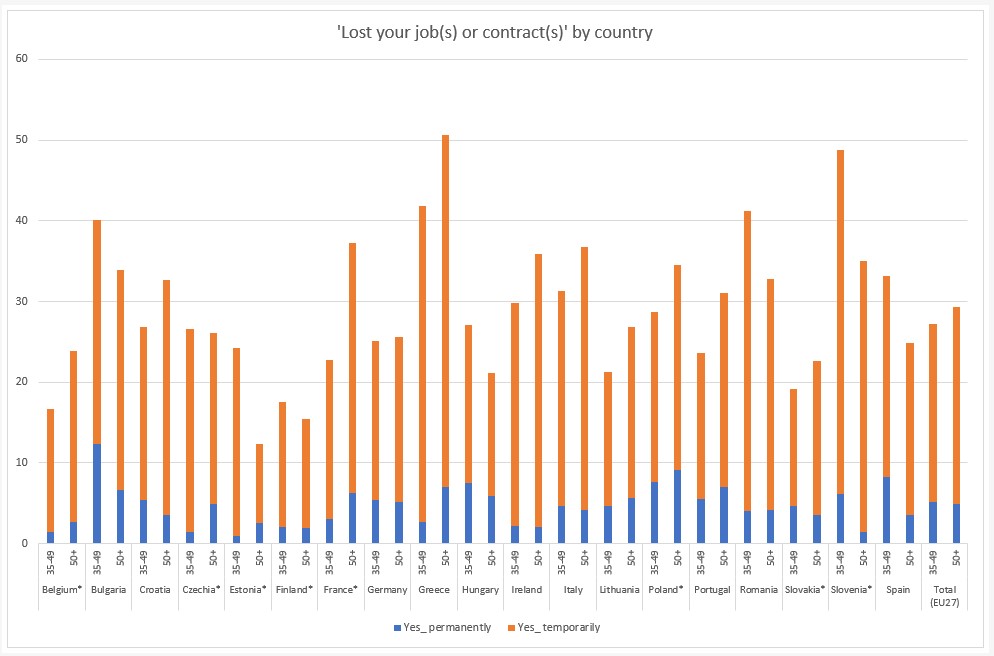

Without having an exact number, we can only roughly estimate the impact of coronavirus on our labour markets. The statistics from February and March show a slight increase in unemployment. The expected soaring unemployment numbers could be slowed down by increasing inactivity as people wait to see what will happen (like it was happening in Italy). The hiring processes have been paused or cancelled under the social distancing regulations, and a number of people have decided to stop or pause their job search. We also expect that the following months of lockdown could be much more harmful to the labour market, as companies struggle with the economic conditions. In the US the estimations of those who were either out of work or working reduced hours in April totalled to 43.2 million workers, while the raw unemployment rate reached 14,7%. That is 3.3 times higher than the estimations for March and 4.2 times higher than in February this year. As official data becomes available, we are likely to see similar trends in Europe. As an example, Finland has already reported the doubling of the number of unemployed jobseekers and 14-fold increase of full-time lay-offs in April over the previous year. At the same time, the number of unfilled vacancies at employment services decreased by 28% and the number of unemployed jobseekers aged 50 and over increased by 62%. Similar trend is also visible in self-reports as Eurofound’s initial survey results show that in 12 out of 20 European countries, job loss due to coronavirus was most common among people aged 50 and over.

Source: Based on Eurofound (2020), Living, working and COVID-19 dataset, Dublin, http://eurofound.link/covid19data. Excluded EU countries had insufficient data, data on countries marked with (*) is low reliable.

Whose job is on the line?

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) reports that partial and complete shutdowns impact primarily retail and wholesale trade, professional and real estate services, transport, manufacturing, hotels, restaurants and air travel. As some of these sectors can be associated with part-time opportunities, apprenticeships and vocational training, they’re likely to also include a great proportion of younger people. It stands to reason why many countries have expressed their worry over the future of their younger generations and the impact of COVID-19 will have on their future careers and finances.

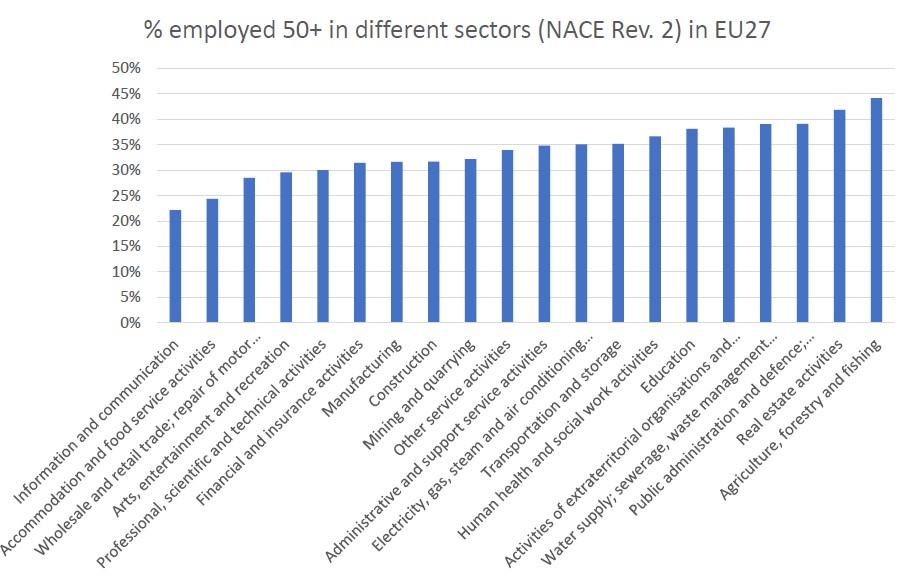

Meanwhile, the pandemic is likely to have major consequences also on the employment and finances of older generations. The sectors that have been hit hard by coronavirus containment measures also employ a significant number of employees aged 50 and over. Getting back to employment can be especially problematic for older generations, as ageism still plays a role in recruitment practices and educational and employment services may prioritise younger applicants who have a statistically higher chance of re-employment.

Source: Based on Eurostat, Employment by sex, age and economic activity (from 2008 onwards, NACE Rev. 2) – 1 000 [lfsa_egan2], 2019

Securing financial futures

As future employment remains uncertain for many, securing financial situations becomes more and more important. Accessing benefits has been delayed in many countries as agencies are receiving a rapidly increasing number of applications over a short period of time. Many countries have introduced coronavirus measures in supporting farmers, entrepreneurs and parents staying home with their children, with European Commission initiating SURE, a 100 billion euro budget to support lives and livelihoods of Europeans. For older generations, access to unemployment benefits can be clouded by eligibility to pension, and they might experience discrimination in receiving unemployment benefits (see for instance cases from Ireland and Israel), and feel pushed out of the labour market towards retirement.

Some older adults may also choose to retire instead of claiming unemployment benefits. In many cases, retirement does not automatically mean inactivity, but many retirees make use of their pensions as a financial ‘safety net’ to start their own businesses, engage in volunteering or continue working fewer hours.

What next?

As the situation continues and societies adjust to the new ‘normal’, many employees and companies are yet to experience the impact of coronavirus. Researchers from the UK have depressing news, as they report that within one-month coronavirus has destroyed the past five years of work towards better employment rates, and the current unemployment number is likely to increase by half. Based on Eurofound’s report, a significant number of workers expressed concerns over losing their jobs in the next three months – 14.5 % in the EU, ranging from 4 % for Belgium to 27.8% for Bulgaria. Early reports from the US also suggest that the early exit trend is raising its head again as the labour market becomes even more unpredictable and unstable. Only time will tell how the increasing unemployment rates will change our labour market and how long it will last.

Our economy might be salvaged within a year or two with massive cuts on many budgets, but it leaves a question, how long will it take to repair the damages done to our efforts to extending working lives and create age-inclusive work environments and workspaces.

______

Katri Keskinen is a doctoral researcher at Tampere University and a member of Gerontology Research Center, Finland. Her work within EuroAgeism focuses on the dynamics of ageism and individual agency in labour market decisions, career and retirement trajectories after redundancy and the role of institutional ageism. Read more on her work here.

Maria Varlamova is a PhD student at the Jagiellonian University, Poland. Her research addresses the employer’s perspective and age management practices, and the effect of the legal environment, economic cycle or welfare regime characteristics on it. More information can be found here.