By: Maria Varlamova & Katri Keskinen

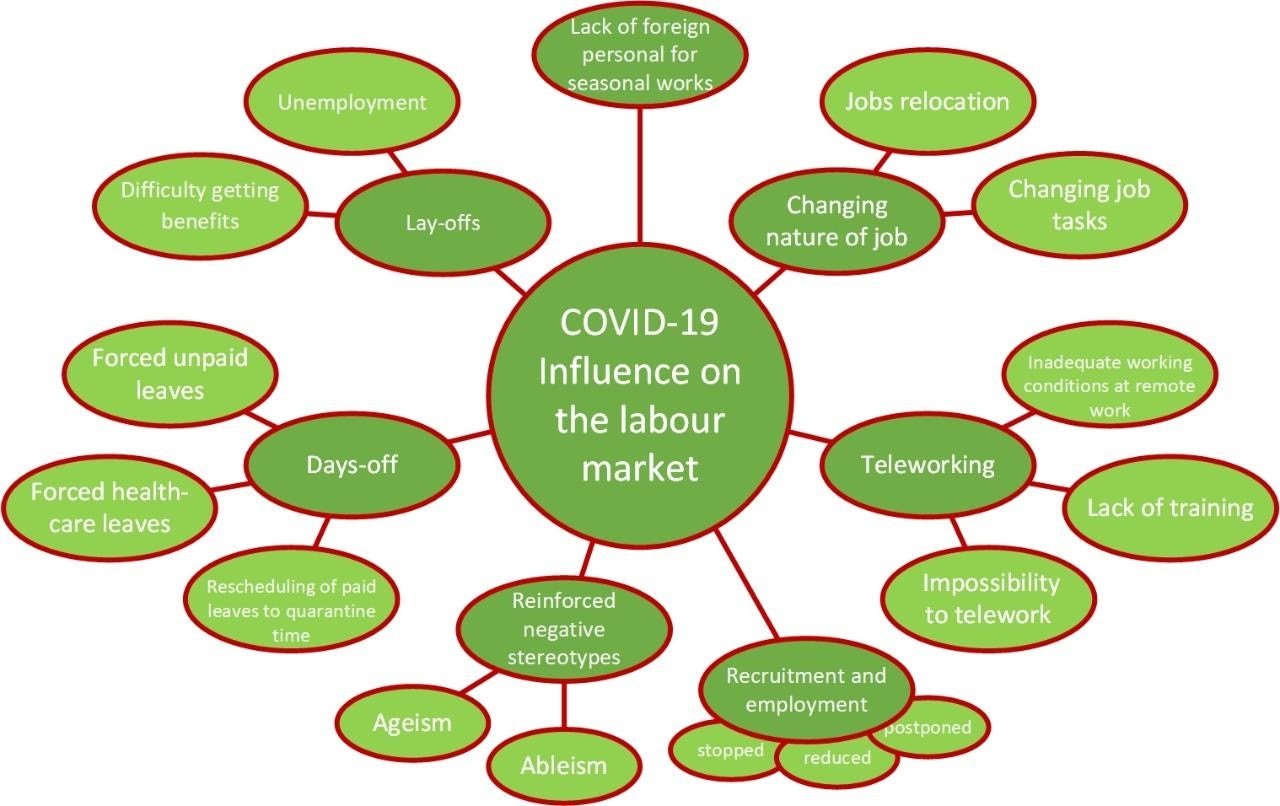

COVID-19 has led to significant changes in our working and consumer lives. Many workers have been laid off either temporarily or permanently, and those able to work remotely have been encouraged to work from home, struggling with increasing work demands and decreasing efficiency. Holidays and other paid leaves have been rescheduled to minimize the economic losses of companies, and employees are unable to travel to their long-awaited destination holidays.

Businesses unable to function normally such as restaurants and cafés have been forced to change the nature of their services from eat-in services to food deliveries and take-away options. Smaller business owners and entrepreneurs may have taken odd jobs to fill their empty schedules to meet the expectations of the new reality. And farmers face the lack of seasonal workers from abroad as travelling restrictions continue.

While the farming industry suffers from lack of workforce, other areas of work are facing larger unemployment rates as factories have been closed and services have become limited. Closing of public spaces has also limited access to working spaces and customers. This is especially affecting informal employees who might not have a permanent workplace or the ability to work from home.

With the closure of services, many companies have also stopped or postponed recruiting new workers. ILO predicts that working poverty is likely to increase significantly within the upcoming months. During this time access to unemployment and other welfare benefits has become increasingly important. Yet, with the growing number of benefits claims the services are likely to be overwhelmed with work, leading to even longer waiting and processing times.

There are, of course, also sectoral differences. We have witnessed requests for retired healthcare personnel to return to their previous occupations at the risk of contracting the virus themselves. At the other end of the spectrum, we have the essential workers for our consumer identities, at risk of losing their jobs. ILO estimates that at risk are especially accommodation and food services, manufacturing, wholesale and retail trade and real estate and business activities.

What about older workers?

The consequences of the COVID-19 crisis are disproportionately affecting older people, especially those with the lowest pay. Older workers are more likely to work in sectors that have shut down or reduced activity and are less likely to work from home [1,2,3]. The lack of appropriate work ergonomics and technological training challenges the learning and work environments for all ages but can be especially problematic for older workers.

A number of entrepreneurs and older workers working past their retirement age have faced age-specific self-isolation restrictions and recommendations that could also affect their ability to work. It comes as no surprise that a recent survey from the United States suggests that COVID-19 has led to increasing numbers of early retirement decisions. Alongside early retirees, the survey points out that more people with care duties and disabilities have now chosen to drop out of the workforce.

The negative ageist and ableist beliefs have been reinforced by the COVID-19 discussions highlighting certain groups as vulnerable and risk groups. Added to the pre-existing stereotypes of older workers as being too expensive, less hard-working, and less adaptable to the latest trends, ageism in the labour market grows stronger. In the absence of dedicated training, resources and measures that ensure the option of remote work, older workers might find themselves pushed out of the workforce, turning ageist images into a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Before the pandemic, we observed an encouraging tendency to work longer — both because people wanted it and because they needed it. Now the efforts to change the work environment, policies and practices to support and enable longer working lives have become even more important. COVID-19 has changed many things in our lives, including how and where we work. Within the pandemic, there is a great risk that COVID-19 will not only strengthen the pre-existing social and regional inequalities, but also the inequalities based on age. By exposing ageism and reacting to it, our actions could define, whether the crisis will move the labour market a step towards age diversity or several steps back.

Further reading:

European Commission’s overview of country-specific measures to protect jobs and economy https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/coronovirus_policy_measures_7_may.pdf

____

Maria Varlamova is a PhD student at the Jagiellonian University, Poland. Her research addresses the employer’s perspective and age management practices, and the effect of the legal environment, economic cycle or welfare regime characteristics on it. More information can be found here.

Katri Keskinen is a doctoral researcher at Tampere University and a member of Gerontology Research Center, Finland. Her work within EuroAgeism focuses on the dynamics of ageism and individual agency in labour market decisions, career and retirement trajectories after redundancy and the role of institutional ageism. Read more on her work here.